A low-speed chase continues for a full mile with the pedicab swerving wildly in the downpour, its owner in wet pursuit. Laurent follows but keeps his distance. The thief could have a gun. This is Texas, after all.

Soon a second pedicab driver pulls up alongside Laurent, and when they round the corner onto Broadway Street they find the stolen pedicab empty. The passenger has vanished. The thief steps out of a house. Does he have a gun? No, he doesn’t. Instead, he pleads with Laurent, promising he’ll return the pedicab. Laurent tells him it’s too late.

“Well I’m just going to wreck it!” the thief yells.

Police cars box in the street, now awash with red and blue light. The cops question and cuff the crook while Laurent berates him.

The thief tells the police he swiped the pedicab because his girlfriend complained about walking home. The Denton Record Chronicle will later note that the man “had no answer to the question of why he didn’t just hire the pedicab.”

He should have. Rides are free.

In a drinking town with a college problem, one immigrant entrepreneur and his entourage roll out a novel business scheme: transport people, charge nothing. Tips appreciated. But after a year in business, Laurent Prouvost still faces a continuing dilemma: how to fill his roster with drivers, fill his fridge with more than condiments, and fill his pockets with more than a pack of Camels.

THE GREEN FLAG DROPS

It’s 2009, a sunny day in December, five months before the Grand Theft Pedicab Incident and one month after Laurent returns to Texas from France with his estranged second wife and their three-year-old daughter.

Traffic sings down Interstate 35 near Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Denton. Laurent and a band of local artists help unload three glossy pedicabs from an 18-wheeler. The vehicles travelled over 800 miles from a factory in Broomfield, Colorado and cost Laurent a total of $14,317.

Once unpacked, the young men take turns laughing and spinning donuts in the parking lot on the new pedicabs. As the caravan rides toward Laurent’s home it hits a hill. Laurent’s so winded he has to stop. This may have been the first indication that Denton Pedicab would prove more difficult than expected.

But that’s not really where this thing starts. Back up about seven years

.It’s 2002 and Laurent moves to Texas from the palm-laden Maldives after meeting his second wife: she’s a young American on vacation, he’s a scuba instructor who takes tourists “under the sea for looking at fish.” Once in Texas, Laurent lugs pianos and armoires for a local moving outfit. It’s amidst the sweating, blistering summer heat that he has the epiphany, a Field of Dreams “build it and they will come” vision of profitable pedicabs servicing Denton at no cost to passengers save what they’re willing to pay.

Hold on a minute. That’s not really where this thing starts either. Rewind. More. Keep going. Back up a full 19 years.

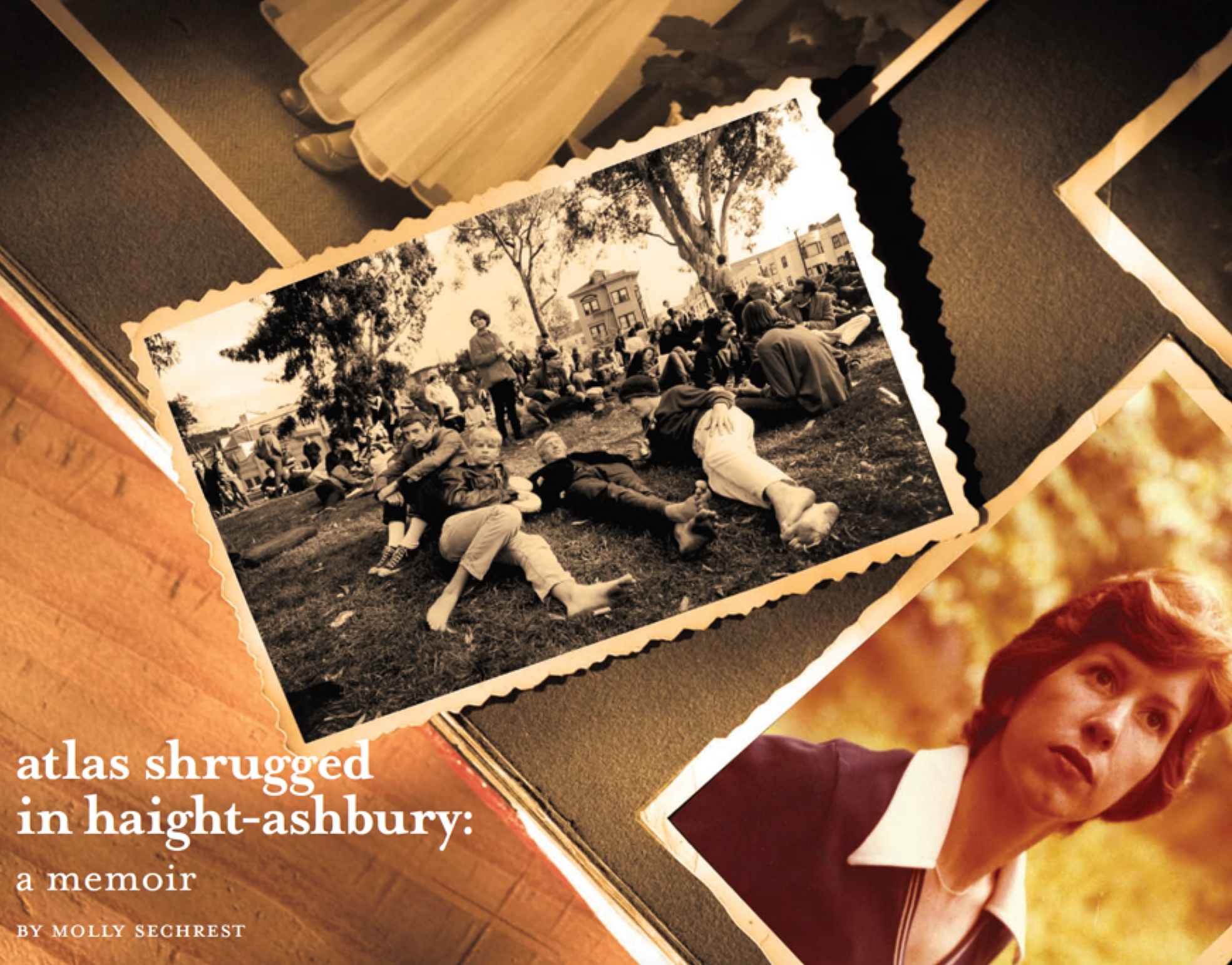

There—the photograph: time has faded its color into an almost pastel gamut. Just look at it: Indonesia, Jakarta, a rural street, 1983. You can almost hear the moped passing on the left. The pedicab’s short shadow chimes noon. The dark-skinned driver in his white t-shirt looks irritated, but maybe he’s just squinting into the sun. His passenger is a 6-year-old French orphan on vacation with adopted parents. He wears clean shorts, a button-up shirt and tiny flip-flops that barely skim the floorboard. The boy ignores the camera and twists in the seat to gaze up at the pedicab driver. The shutter clicks.

In 27 years that little boy will start Denton’s first pedicab service.

And in the interim he will quit an apprenticeship as a barber and become a scuba instructor, an aquatic globe-trotter. In Madagascar he will swim with sharks; he will have an air-pocket in one of his fillings explode a tooth during an especially painful ascent and he will save a panicked Englishman from being hacked to bits by a boat propeller. In Sri Lanka he will walk with elephants and later he will father a boy of his own. In time he will divorce, remarry, and save up a nice chunk of cash while running a tattoo parlor in France before his second marriage sours and he returns to Texas.

His latest undertaking—this pedicab business—may prove the most arduous, hair-raising venture of Laurent’s life.

THE BUSINESS OF BUSINESS

In February 2010 Laurent lives alone in a post-war two bedroom house near the University of North Texas. Two squares of hemp cloth hang on his living room wall bearing the handprints of his first child—now a teen living in France with his mother—and the footprints of his second child who lives just down the street with her mother. An adjacent wall bears a large Rastafarian-themed tapestry showing a wind-swept lion’s head. The house is tidy... maybe a bit Spartan, but very tidy. Over the next year Laurent will rearrange the furniture no less than five times.

On a dining room table rests a spiral notebook detailing Denton Pedicab’s company architecture with impressive titles: operations manager, advertising director, sales representative, maintenance director, etc. In this makeshift home office with its dry erase boards and spare bicycle tires, Laurent gesticulates wildly with a big smile and details his business strategy. It breaks down like this: pedicab drivers volunteer for shifts, lease the pedicabs, and work for tips. Commanding prices to passengers is strictly forbidden. And while established pedicab companies in, say, Austin charge around $40 a shift to lease a pedicab, Laurent now charges his drivers one dollar per hour or $10 for a typical shift.

So the pedicabs generally run in two shifts: 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. and then from 5 p.m. to the wee hours of the morning when the bar crowds scatter. While drivers are encouraged to mingle and bring personality to their professions, drinking on shift is prohibited. And take care of the equipment. Go slow. Buckle up your passengers. No more than three passengers at once. Use your turn signals. Be safe. Be situationally aware: that pedicab’s 10 feet long. Stay off campus and within the established boundaries.

The nucleus of these boundaries is about three square miles around the University of North Texas, Texas Woman’s University and downtown Denton. Given this area, Denton Pedicab’s dedicated core of drivers have become urban geographers: they know potholes, fissures and hills. They know that the least direct path to a destination might be the easiest and some hills are sadly unavoidable.

By day pedicab drivers cruise bustling university outskirts and Denton’s idyllic courthouse square—anywhere there’s foot traffic and the opportunity to call out to pedestrians: “Need a ride? Need a ride? It’s free.”

But some shifts, especially Sundays and Mondays, are difficult to book because they are much less profitable than weekend nights. Overall, most drivers claim they’re really only transporting passengers 20-30% of their time spent on shift, the remainder being delegated to loitering, socializing and people-watching.

Perhaps this is because pedicabs are not entirely accepted as legitimate transit in Denton, a town still warming to their utility even if pedicabs are accepted as the norm in their birthplace, Asia, and in many American cities including Seattle, San Diego and New York City.

While waiting for potential customers outside of a local bar late on a Saturday night, Denton Pedicab driver Nathan Weiter, 22, says “A lot of people won’t ride for free because they feel bad not tipping. But I always try to tell them that it’s cool. Because whatever I’m giving you, just pay it forward.” Whoa, is this a business or a charity? Do fuzzy, feel-good sentiments make up for empty pockets?

Later that night, Nathan will save two 21-year-olds from themselves after a police officer finds them urinating on a car. Nathan will give the men a ride home and in return they will give him all of their cash.

But hefty tips are not always the case. In fact, Denton Pedicab drivers estimate they receive tips from 50% of their passengers. In addition to having been tipped zilch for wicked cross-town jaunts, they’ve been compensated in everything from fruit to cigarettes and proposed sexual favors. Recently, a driver with five bucks in his pocket hauled a young couple one mile from Fry Street and found himself riding away with $95.

THEORY MEETS PRACTICE

Low-profit days give way to high-profit nights when bar-goers are uninhibited or desperate, desperate because Denton suffers from a transportation void: its lone taxi service is notoriously unreliable and does not run 24 hours. Drinkers can either bum a ride, chance a ticket walking home or defy reason behind a steering wheel.

Denton Pedicab hopes to fill this void by plying the college bars which draw throngs of thirsty students every weekend. “On Thursday, Friday and Saturday it’s vacation,” Laurent says. “From 10 to 2 a.m. they’re on vacation.”

For now, the Fry Street area brings Denton Pedicab the most business. A chalk outline of its former glory, Fry Street is still a three-block, liquor-slick theme park boasting cheap drinks for fresh 21-year-olds, those who wish they were and all those in between. It’s a place where young men smell of cheap body spray and silk-skinned girls in heels click erratically down sidewalks as the night wears on and the poise wears off. Some wander in and out of this world and some get lost. A local bartender once called its three most popular pubs “The Barmuda Triangle,” and it is here that pedicab drivers put in their hardest work, physically and psychologically.

One weekend night near the center of the triangle, Denton Pedicab driver Will Frenkel, 21, is solicited by “two 300-pounders and a friend.” The trio is far gone and jam into the pedicab’s 41-inch-wide seat like giant marshmallows. The safety belt won’t reach across their laps but they’re in no shape to drive, plus they’ve already forked over $25. Will spins the grip-shifter to a low gear and digs into the pedals.

With a block behind them, one of the 300-pounders starts falling out of the pedicab. Will stops. They regroup. When they start up an incline the pedicab stops again. Will weighs 150 pounds, the pedicab weighs more, and together they’re hauling over 700 pounds of slurring meat and bones. Will strains to power forward but gravity can be so cruel.

He calls for backup. Laurent arrives in another pedicab and rides off with $10 and the lightest passenger. Will starts picking up speed when the fight erupts: one guy wants to go home, the other wants to hit a house party. They argue back and forth, back and forth. Exhausted, Will obliges both requests, but not before one of the men opens wide and vomits down the fiberglass sides of the cab and then pumps more onto the pedicab’s floorboard.

A barista at a coffeeshop gives Will a pair of plastic gloves and cleaning supplies before he returns to the bars to shuttle more drinkers. Was it worth $15? According to Will, “It all adds up.”

But playing the odds has done little to lower Denton Pedicab’s attrition rate. The job has ground over 40 hopeful drivers into washouts. A number of factors influence employee retention; for one, like college coursework to local students, pedicabbing is grueling work with no guarantee of adequate pay. (Denton Pedicab drivers say the job has forced them to lose weight where it wasn’t wanted and vice versa.) But moreover, novice riders hit the streets expecting fast cash without strategizing, like knowing where to find receptive customers, which bars have popular drink specials on which nights. Or another strategy: using text messages and Facebook to pull in extra income. Many new drivers work the job for one or two shifts without throwing down a sliver of initiative and then never return.

Laurent is banking on local entrepreneurs to promote their businesses on his pedicabs and therefore help promote Denton Pedicab. Laurent’s had some success with this approach, mainly with local bars and restaurants. While Denton Pedicab continues to refine its pricing, it currently offers promotion through pedicab-mounted magnets, decals, large aluminum signs and full vinyl wraps. A 10”x4” sticker runs $30 a month. A 34”x20” aluminum sign mounted on the back of a pedicab goes for $2.50 an hour.

Denton Pedicab’s greatest success has been advertising three major college bars on Fry Street for a total of $18,000. The contract not only includes advertisement, but committed pedicab service on weekend nights. Despite the price, it’s not a bad idea for the bars: there’s less liability if patrons think to get home in pedicabs instead of cars.

But of the businesses surveyed who have advertised with Denton Pedicab, there’s a common consensus: it’s expensive. While Denton Pedicab has obtained new advertisers in the last six months, others have allowed their contracts to expire with no current intention of renewing.

With lease prices very low and advertising prices high, does Laurent expect to get rich? Better yet, does he even want to get rich? “I want to be super rich,” he says laughing, but with this caveat: “Money's just a tool to have access to have different things, but it's not a must. You can live without money. It's maybe hard, but money's not everything.”

Beyond personal profit, Laurent says he wants his business to provide an important community service. Laurent adds he wants to drastically boost Denton’s pedicab population, turning the town into “Pedicab Valley.” Until the City of Denton drafts an ordinance against such an influx, Laurent is only limited by money and vision.

So, does this sound like the work of your average tree-hugging, one-world-one-love, kind of dude? Well, it isn’t. Not exactly anyway. Laurent is not so easily boxed. For one, though he’s been championed as an agent of the Green Movement, he doesn’t believe in global climate change or that he’s part of any movement: “I don’t want to be against cars or against Red Bull or Coca-Cola... There’s still some plastic on my pedicab. If people think, He’s Green! He’s Green! Then they don’t look at the whole picture.”

Then there’s the issue of corporate encroachment near inner-city Denton. While the Great Recession has drained much of the country, Texas has been largely spared. Denton County is one of the fastest growing parts of the nation, and while many townsfolk wish to preserve its quirky, locally-owned charm by staving off the corporate sprawl that has engulfed much of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, Laurent welcomes it. He could use the ad money.

A BALANCING ACT

On Easter Sunday Laurent is hosting a barbeque at his home for about a dozen friends and pedicab drivers. By mid-afternoon festivities have included tree-climbing, bicycle riding, a quick pub crawl, and heated games of foosball. Laurent plays the game with a distinct style, finesse, and intensity. He curses his blunders in French but is keen to outwit his opponent through psychology, trickery, and accuracy when the ball whizzes past that plastic goalie with a SMACK!

It’s during these times of R&R that you get to see what kind of a guy Laurent really is: he’s the kind of guy who rewards his employees with tattoos; he’s the kind of guy who lies in the middle of a street bare-chested in wait of the skateboarder about to fly overhead. And he’s the kind of guy who likes to joke and laugh but whose eyes get dodgy when asked about his patience level with the business or about his hopes for netting a decent salary in the near future. He says with conviction that he believes in the work he’s doing, he then looks you straight in the eyes and says, “It drives me nuts sometimes.”

But this is a BBQ, a time for grilling meat and draining canned beer.

One of Denton Pedicab’s drivers, Will Winkler, 27, walks into Laurent’s back yard carrying a braided slackline which he strings up between two trees. Once secured, people take turns trying to walk the tightrope.

When Laurent gives it a go, he falls off immediately. He tries again and falls. He tries again and falls. On his fourth try to take a single step he slips off the slackline and lands on his back. “Are you okay?” someone says. He gets up laughing.

Laurent can’t walk the line alone and it’s not until he steadies himself by tightly gripping a pedicab driver’s shoulder that he takes a step forward. This same principle applies to Denton Pedicab, and Laurent knows it.

THE RIDE AHEAD

Now, with a full year of local service to his credit, Laurent and his young company have a new opportunity ahead. With expected completion in June of 2011, Denton County will host five railway stations that will link it directly to Dallas. The A-Train, as it’s called, will run until 11 p.m. on Fridays and 12 a.m. on Saturdays. What does this mean for Denton Pedicab? Business—pedestrian, corporate—and equally important: hope for greater economic sustainability through advertising.

At 35, Laurent’s suffering the pain of patience, the pain of entrepreneurship. If it’s true that most upstart businesses demand years before spinning a significant profit, then true to form, Laurent Prouvost and his intermittent band of pedicabbers have an uphill ride, a ride with a couple, possibly-queasy 300-pounders packed in the back seat and no guarantee of adequate profit. But hey—no matter how much it is, it all adds up, right?