She stood on a bank of snow with an outstretched hand and decades of hope. It had snowed for seven straight days and three-foot drifts lined the tiny town. The woman walked the streets every day, inching along on a cheap wooden cane. Her feet were wrapped in cloth tennis shoes. She wore flowered dresses and draped her head in scarves. Her face was the color of sandpaper and creases had etched their way around her eyes and cheeks years ago.

On this day, she stood next to the entrance of a hotel. We filed past her, bundled in long wool coats and caps and bleary-eyed from a long night of celebrating. My friends, the Armenians, spoke in excited, broken English about our plans to reconnect. Each person crunched their way through the snow and hauled their luggage onto a bus, barely glancing her way. Thoughts of liberty, freedom, and possible futures filled our minds; the woman was merely a shadow to us. When the last person boarded, the driver shut the door and the bus slid its way down the hill and wound its way through the narrow streets. The beggar remained behind with her feet and cane planted in the snow, hoping for a deliverer.

WHILE THE WORLD HAS BEEN CAPTIVATED by the Jasmine revolution that began in Tunisia and spread across the Middle East, a much quieter change has been unfolding in Armenia, a country tucked between Turkey, Georgia, Iran and Azerbaijan. It’s a place that has been racked by genocide, devastating earthquakes and never-ending wars in the last century. Not even 25 years ago, it was still under the rule of the Soviet Union. Elderly citizens wander the streets with blank expressions and live with a “what-if” mentality. They speak Russian first, Armenian second, and seem lost in thoughts of yesterday. Gunfire cracks in the air along the border of Azerbaijan. Buildings with no roofs or no windows dot the highways and cities and stand as reminders of the abrupt departure of the Soviets.

In February, an American named Glenn Cripe came to Armenia to teach young adults about liberty and entrepreneurship. He brought another American, a Norwegian, and a Pole to help him conduct this “Liberty English Camp”—a project of the Language of Liberty Institute. The camps, first begun in 2005, offer young adults the opportunity to increase their knowledge of classical liberal ideas and to actively participate in discussions and debates on capitalism. The students in Armenia were also to receive training in the practical application of these ideas to real business practices. In addition, the students enjoy using the camp as an opportunity to practice their English speaking skills.

The night the instructors arrived in Yerevan, our host, Zara, took us to a local restaurant. The wine was served in a hand-carved wooden pitcher, and we drank from hand-carved wooden cups. In between sipping wine, discussing individualism and eating pickled carrots and dolma (a delicious mixture of rice, spices, and beef wrapped in grape leaves), we listened to a local band play folk music.

At the end of the night, we hauled our luggage into a taxi and took off for the ski resort town of Tsakhkadzor, the location of the camp and home to some 1,500 residents. Tsakhkadzor is an hour northeast of Yerevan, and sits at an elevation of approximately 8,500 feet. There had not been a significant snow yet, and the hotel was dark and deserted.

Because no one else was staying here, the manager had turned off the heat and hot water. He had forgotten about the few of us coming early. Zara asked him to turn on the heat; we thought for sure the rooms would warm up quickly.

A quick meeting and a bottle of wine later, the rooms were still not heating up. I huddled under thick blankets and wore my jeans, socks, and shirt. Glenn Cripe, the founder of the camp, slept in his scarf and toboggan.

One by one on Thursday, the campers began to arrive. This was to be a truly international group. There were two Georgians, many Armenians, an Indian, an instructor from Norway, an instructor from Poland, an instructor from the U.S. who moved to Estonia, and one man who travels so often, he calls himself a “resident of the world” and says he pays no income tax to any country.

After we’d traveled back to our home countries and readjusted to our routines, plans were being drawn up for other camps.

The movement was growing.

FOR THE NEXT SEVEN SNOW-PACKED DAYS, about 30 students explored the historic arc and vistas of classical liberal thought and learned how its ideas can be applied in everyday life. Instructors taught about the historical development of classical liberal thought, and the ideas of luminaries like American philosopher and novelist Ayn Rand (1905 - 1982), famed Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992), and the French economist and statesman Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850). Presentations were made on free market economics, human progress, the origin of rights and the proper role of government (highlighting Rand’s work), the meaning of money, and the moral basis of capitalism. Some of the campers are not libertarians, but centrists, statists, liberals. Myths about capitalism were explored and students debated.

Practical workshops on entrepreneurship were held throughout the week, with a focus on learning how to create viable business plans, understanding financial modeling, and effectively executing project assessment and management.

The students were tasked with synthesizing all of this information and creating, by the end of the week, their own business plans, which were presented to their peers and instructors for evaluation.

At night after dinner, we stood in three-foot drifts of snow, drank Armenian wine and Russian vodka, and discussed the presentations of the day. We watched movies about entrepreneurship and liberty, including the Acton Institute’s Call of the Entrepreneur and The Singing Revolution. Then into the wee hours of the morning, we discussed philosophy, classical liberalism, and business plans, while sipping the famous Armenian cognac Dvin, which Winston Churchill was known to favor.

At times, the English barrier was a challenge. A young blonde Georgian said he was going to make the most beautiful toast in the world, and while standing under a gazebo at 4 a.m., with the snow falling around him and a plastic cup of vodka lifted to the moon, told me, “The beauty of the nature is the enema.”

He meant animal.

While the students had their fun, many took the lessons seriously. This same Georgian wore an American flag patch on his knit cap and passed around his father’s advice like it was the law: “If you want to be successful in life, it depends on you,” he told everyone.

One woman who grew up in a war zone knew the Georgian’s words to be all too true.

YOU WOULDN'T THINK GLENN CRIPE would be the sort to start revolutions and movements oceans away. Despite his 61 years, he has a boyish face and head full of salt and pepper hair that’s cut in a conservative, almost schoolboy style. He laughs frequently, has a penchant for good wine and pl1ays classical piano. He’s short, with broad shoulders that he likes to cover in plaid shirts and a navy blazer. He has a laidback manner, but can be stubborn when he thinks it’s necessary – like refusing to go to the hospital in Nigeria when he fell into a drainage ditch and bruised his ribs (he was scheduled to go to Armenia the next day and didn’t want to delay his trip).

Glenn wouldn’t tell you he’s trying to start a movement, either. “I don’t consider myself a political act,” he says. “I’m into spreading ideas.”

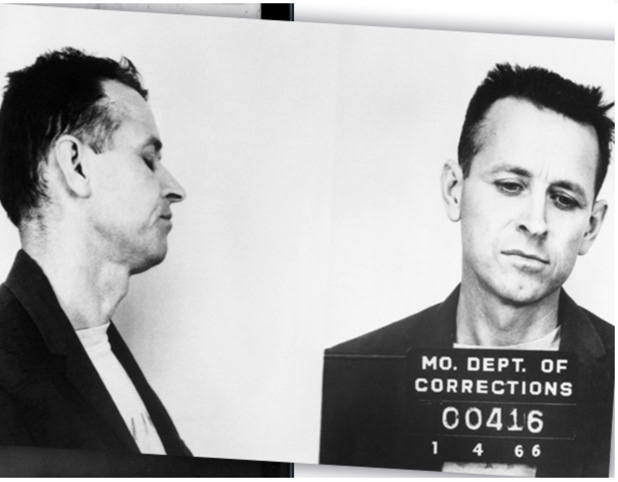

He was born in the suburbs of Chicago into a middle class family with conservative beliefs. Because of his father’s job, he lived all over the U.S., which he credits for giving him a sense of adventure. He wasn’t good at sports, so he lost himself in books instead. He was an Eagle Scout and enjoyed camping and hiking. It wasn’t until he was nearly finished with college at Indiana University that he began reading about business and economics. One year he was there, the campus was filled with demonstrations on communism and the Vietnam War. When he went home for the summer in 1970, his friend gave him a copy of Ayn Rand’s Anthem as he boarded the plane. “Here was this little world of clarity and individualism,” he recalls. He read all of her works in three weeks, and then moved on to Hayek, Harry Browne, Milton Friedman and Frédéric Bastiat.

“Reading Rand inspired me to question more,” he says. “She was the first writer who helped me understand and sort out my own ways of thinking so I could better analyze and understand the world. Here was a voice of reason that cut through the fog and said, ‘This is how the world works.’”

He wanted to be an international banker and combine his love of travel and economics, but he says he soon realized 22-year-olds don’t land those types of jobs. He knew he was good at math, music, and foreign languages (which require strong skills in logic and pattern recognition), and he knew that the growing IT field required those same core skills. He took a computer programming aptitude test, earned a high score, and was subsequently hired and trained by a Richmond software development firm.

In 1990, Glenn attended his first International Society for Individual Liberty Conference (ISIL). Returning to the conference every year, he soon met Stephen Browne and Virgis Daukus, who founded the first Liberty English Camp in Lithuania in 1997 to give students an opportunity to practice discussing libertarian ideas in English before attending ISIL conferences. Jaroslav Romanchuk, director of the Mises Scientific Research Center in Minsk, started bringing Belarusians to the camps, and in 2004, Glenn and Andy Eyschen became camp instructors. In May 2005, Glenn registered the Language of Liberty Institute as a nonprofit organization in Arizona with the goal to continue the camps and to expand them to new countries. The institute’s mission is to “prepare individuals to develop the civil institutions of free societies.” Since 2006, the Language of Liberty Institute has launched camps in Ghana, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Nigeria, Poland, Slovakia, Portugal and Albania. This year will be the fifth year for Slovakia and the fourth year for Poland. For each camp, LLI works with local partners, who usually are former camp students.

Last year a young Armenian woman named Inessa Shahnazarova attended the camp in Poland. Inessa is petite, with dusky skin, thick black hair, dark eyes and a perky nose that tilts slightly upward. She wasn’t a libertarian before the camp, but as she listened to the lectures, she says she began thinking about what liberty could do for Armenia.

“I knew we should encourage this generation of Armenians to contribute to the betterment of Armenia and the prosperity and development of Armenia,” she says.

She stayed in contact with Glenn and began organizing activities and researching hotels that would offer good rates for the camp.

She took applications from Armenians, Georgians, an Indian, and a Nigerian, and selected about 30 students that seemed serious about liberty. She drew up plans to educate them with lectures such as “The Moral Basis of Capitalism” and “The Proper Role of Government.” With the help of the instructors, she selected movies such as The Soviet Story and John Stossel’s Greed and Are We Scaring Ourselves to Death?

Finally, in February, the time had come.

FOR HER, WAR WAS LIFE. Manane Petrosyan was 12 years old when her family moved into a hole in the ground. It was 1992, and the fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh, a region just east of Armenia, had taken a violent turn. Manane was a bright child, with curly dark hair and amber-colored eyes. She shared the space in the ground with seven other families, and in the mornings, they sat on carpet and listened to the planes pound the city with bombs. All the people in the ground were women; the husbands and sons had already died in the war or were fighting in it. They sat solemnly and stared at dirt walls and thought of the dead. When it was silent, they climbed out of the hole and walked outside. The burned-up buildings simmered like coals and there were no leaves on the trees that were still standing. Ash covered everything. “Everything was grey,” Manane recalls.

For two years, she lived in the ground. Her cousin visited the shelter one day, and took Manane to a town in Armenia where she began attending school. She had no contact with her family. The blockade that Turkey and Azerbaijan had put on the country left them with no electricity, hot water, or telephone service. Thirteen months later, she saw her mother in the yard playing hide and seek. She had come to take Manane home.

Planes were still dropping bombs occasionally, but fighting had largely subsided. During a birthday party at a friend's house, when some planes flew low overhead, Manane and another little girl dived to the ground, hands covering their heads. In their young, war-stricken minds, they were sure they were about to be bombed. When the planes disappeared, they stood up. Dirt clung to their dresses and hair. “All I was thinking was to be alive,” Manane says.

Years later, she remembered this incident with distinct clarity. It was traumatic moments like these that led her to a liberty camp in Tsakhkadzor on a snowy February day

Joshua (at left) and Givi.

THE STUDENTS SAT IN ROWS of chairs in a room with lime green and pale orange walls. They’d all arrived in Tsakhkadzor, and on the first night, were watching The Call of the Entrepreneur. Most watched the documentary intently. Instructors Glenn Cripe and Joshua Zader surveyed the students’ interest and asked questions. There were a few who passed notes, and one young man with thick black eyebrows dozed in a corner.

Throughout the week, Glenn, Andy Eyschen, Joshua, Jacek Spendel, and Thomas Kenworthy took turns presenting lectures on the history of classical liberal thought, how to create business plans, the proper role of government, and even transhumanism.

Givi Kupatadze, a Georgian, was one of the stars. A blonde-headed, blue-eyed romantic who wrote love poems in broken English, Givi didn’t necessarily set out to be a ladies’ man, but throughout the camp, the women flocked around him. It wasn’t just his handsome face that attracted the women. At 22, he was in talks with an agency to publish a book, he’d made presentations to the ex-minister of finance, and he’d created and was close to selling a customer program for grocery stores.

He was born into a family that lived through the Soviet times and had been affected heavily by the stifling atmosphere. Givi’s father watched the “successful people” rise in ranks of the mafia, and once commented cynically that there were only two ways to make it—by running guns or by becoming the “boss of the clan.” But his father did always preach, “If you want to be successful in life, it depends on you, and you must take good education.” And Givi never forgot that.

Givi earned a scholarship (which was nearly unheard of in Georgia, especially before the revolution in 2004) to study economics at Tbilisi State University. He attended conferences and made presentations on how to lower, and even eradicate, unemployment in Georgia. In 2008, he read a book by Jim Rohn called Seven Srategies for Wealth and Happiness, and decided to become an entrepreneur. “I want to improve people’s lives,” he says. “This is my passion in life.”

When he attended the first liberty camp in Georgia in 2010, things fell into place for Givi. Before, he’d always felt under obligation to help his friends and neighbors. After the camp, his thinking changed. “I realized that I own my life and no one has the right to make demands on my life,” he says. “And I have no right to make violations against others. It was amazing for me.”

Watching these kinds of realizations take place is exactly what drew Joshua Zader, one of the teachers, to the camps. “There’s something really fascinating about students who want to learn these principles,” he says. “They don’t have teachers around them who can teach them. They’re growing up in the shadows of communism. It’s empowering for everybody to learn.”

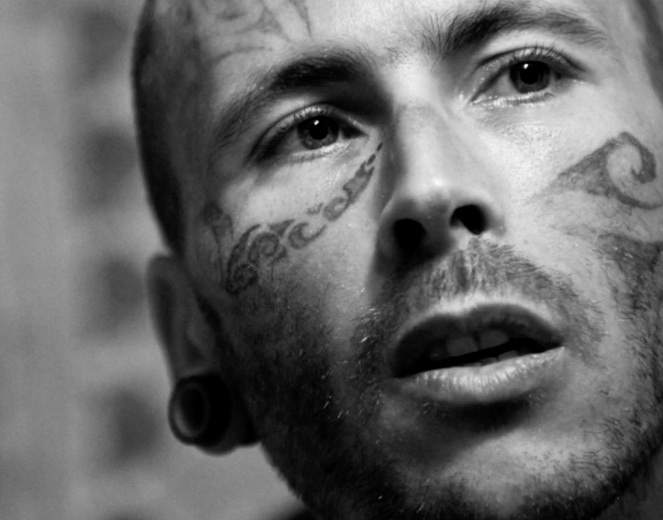

Joshua grew up in Cookeville, Tennessee, where he was an outcast because of his atheist beliefs and “hippie” tendencies. For most of his life, he says, he felt like an outsider. He shares a story similar to Glenn’s when it comes to discovering libertarian ideas. An older friend gave Joshua a copy of The Fountainhead for his 18th birthday. A few months later, he read it. “I was captivated from the very beginning,” he says. “I like books that portray an ideal and that portray something deeply, deeply good. I sensed Roark had high integrity, and that resonated with me really deeply.” He spent months reading everything he could about Ayn Rand. To him, she’s a “system builder” and “provided a framework for understanding ideas like existentialism.”

He became so obsessed, he didn’t know where he ended and she began. He stopped reading Rand for a decade and revisited her works in 2003. He started The Atlasphere, a dating site for admirers of Rand. After his friend Stephen Browne, one of the founders of LLI, told him about the liberty camps, Joshua decided to volunteer his time in Armenia as a teacher.

While his and Givi’s journeys to Tsakhkadzor were relatively painless, Manane’s was not.

AFTER MANANE MOVED BACK HOME with her family, she returned to school in Nagorno-Karabakh. The students had no books, not even maps. The blockade was still in place and she bathed in cold water and studied by candle light. One day, her brother was proceeding to the bathroom, when the bombs started dropping again. He hid under their mother’s skirt. As a result of his terror, he wet the bed until he was 15.

When she was 17, Manane went to Artsakh State University and studied pedagogy and philosophy. For three years, she taught English to Russian children. At 22, she moved to Yerevan to study social work. A professor invited Manane to assist her in her work on an NGO that deals with youth in high-risk family situations. It’s funded partially by the Armenian diaspora in the United States, and is a sister of the Fund for Armenian Relief, a New-York based nonprofit.

After she graduated, she began working full-time for the NGO. She wanted to study social work because of her aunt, who works for the Red Cross. During the war, her aunt sent clothing and food for the communities. She was Manane’s role model. “I think I am not so far from her,” Manane says.

Now, Manane wants to help children in orphanages and children who have been taken away from their families. She’s given her brother therapy and watched his self-confidence improve over the years. Last year, when she heard about the liberty camp in Georgia, Manane applied and was accepted. It was the first time she’d ever heard the term “liberty.” “I am so inspired,” she says. “If we spread this idea, we will have a better Armenia than we have now.”

Not everyone in Armenia will be excited about this movement. The older generation still wants to depend on Russia for protection and economic stability. “They are still waiting for someone to come and protect them,” Manane says. “From the beginning, they didn’t believe we were alone. They were angry with Gorbachev. They cannot go back to Soviet times. They don’t know what to do. I hear all the time from the older generation, ‘During the Soviet Time, during the Soviet time, we were secure.” Manane shakes her head. “The older generation is not interested in liberty. They lived their lives under the control of somebody.”

After Manane returned from Georgia, she contacted Inessa to help organize the camp in Armenia. She had her own agenda, and her own way to spread the word.

WITH THE MUSIC PUMPING iin the background, Apoorv Jain stepped to the left and to the right, his feet kicking in front of him. Apoorv, an Indian student at Yerevan State Medical University, was teaching the Armenians how to dance to the country song “Cotton Eye Joe.” I stayed in the background watching, keenly aware of the irony that I, the American, didn’t know the moves.

This was a celebration of the week’s activities. It was the final day of camp. After an intensive seven days of learning, the students had decided on a grand finale with a talent show, outdoor campfire (keep in mind there was three feet of snow on the ground) and grilled sausages and lavash. While clumps of snow thumped from the roof to the ground only hours before, the students had presented their business plans. The groups had worked all week with the teachers to finesse the details. Standing before his PowerPoint presentation, Givi explained why his group wanted to revitalize an aging theme park in Yerevan and call it "Victory Wonderland." Another group wanted to create a volunteer-run website, "Welcome to the Earth," which would function as an encyclopedia of world cultures. Manane’s team wanted to start a nonprofit that inspired young people to become self-sufficient.

The teachers had gathered in their room to decide which group had the best chance of succeeding with the business.

That evening, after the students sipped on beer and vodka and took pictures of each other on a rickety stage, the teachers offered tips for the projects. The advice was mostly practical: look to the long-term future, do research on your competitors, identify your strengths.

Inessa rested in her room and drank a glass of Armenian pomegranate wine. She’s planning on organizing another camp, but also designing weekly activities to help promote the ideas of entrepreneurship in Armenia. “These views are not very popular in Armenia, but our strength is not in numbers but in our commitment to work together to benefit all of us,” she says. This movement, though it is quite small right now, can grow with time and achieve more and more goals.”

MONTHS LATER, GLENN WAS BOMBARDED with inquiries about new camps. His ability to respond is limited because of time and money constraints. Most of his time in the future will be spent fundraising for the LLI so they can continue to grow. But, “the world is huge,” he says, and young people’s appetite for learning about liberty seems limitless.

In March, tensions escalated between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Officials in Azerbaijan announced that a young boy had been shot and killed on the border by an Armenian sniper. In response, an organization offered sniper training to Azeris in April in preparation for another war. One woman who participated in the training told The New York Times she’d rather “go to war [with Armenia] than wait another 20 years” for a peaceful breakthrough.

If Manane has her way, Armenia will not be going to war again. She sat by a window in the rundown hotel. “There is one thing I can do—I can educate about liberty, make active the new generation. If you can change here,” she says, pointing to her head, “you can change anything. You have to think first.”

Behind her, a flock of blackbirds sprang from a snow-covered tree and flew into the air, their destination unknown.